A Perl script controls Tmux configuration

Magical Window

Instead of manually rearranging windows in a development environment time and time again, the Tmux terminal multiplexer can restore them from a configuration script.

If you don't use a development environment such as Eclipse but mostly rely on the command line in a terminal, you will certainly be familiar with screen. Among other things, this legacy terminal utility ensures that, after network problems, the initiator of an aborted SSH session can continue without problems exactly where they stopped typing. The screen utility sits between users and applications running in the terminal and tricks the application into believing that an attentive user is still at the keyboard, even if they have long since left the office for a weekend break.

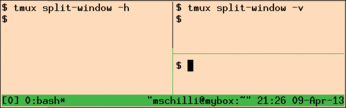

As you know, the Unix world has not stood still over the past 20 years, and a relatively young project named Tmux [2] has been set up to improve and replace Screen. Like Screen, Tmux offers the user several sessions, which in turn comprise windows; in Screen lingo, this does not mean desktop windows, but switchable text interfaces in the same terminal window. Using keyboard shortcuts, Tmux can subdivide each window again by creating vertically or horizontally arranged panes, all of which are visible at the same time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Two tmux commands divide the window into two horizontal panes, and then the right pane into two vertical panes.

Figure 1: Two tmux commands divide the window into two horizontal panes, and then the right pane into two vertical panes.

[...]