Monitor your old Linux devices

Watching Grampa

© Lead Image © lightwise, 123RF.com

Create monitoring dashboards with SSH, command-line tools, and Node-RED.

Some excellent technologies and packages are available for monitoring computer hardware. For medium to large systems, the Simple Network Monitoring Protocol (SNMP) approach is usually the preferred solution. However if you have a smaller system with older or low-end servers, some excellent lightweight command-line monitoring utilities can be used instead.

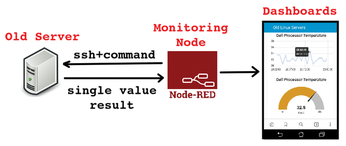

These command-line utilities can be run remotely over Secure Shell (SSH) and the output parsed to return only the key data values, which can then be displayed graphically in a Node-RED web dashboard (Figure 1). In this article, I demonstrate examples that use the iostat utility [1] to monitor CPU utilization and the lm-sensors package [2] and hddtemp utility [3] to monitor temperatures on dashboards.

[...]