Three-dimensional scenes in web browsers with Three.js

Perspective in 3D

HTML5 brings 3D support to browsers. Thanks to WebGL, Firefox, Chrome, and company, you can render three-dimensional worlds without special plugins or viewers, and the Three.js JavaScript library makes programming easy.

Beyond the buzzword "HTML5," a whole bundle of new technologies has found entry into browsers on desktop and mobile devices [1]. Among them is one that opens the door to the 3D world: WebGL. The Web Graphics Library [2] is a JavaScript interface for the OpenGL 3D library. With it, normal HTML pages can include three-dimensional content that runs on the graphics card with hardware acceleration.

WebGL has been implemented in Mozilla Firefox (from version 4), Opera (from version 12), and Google Chrome (from version 9) desktop browsers. Because the Khronos Group used OpenGL for Embedded Systems (OpenGL ES) as the foundation, it also can be used under Android with Firefox for mobile devices and Opera Mobile.

Although the idea to bring 3D applications to the web is not new, all previous attempts like VRML, Java applets with Java-3D/JOGL, and 3D Flash have reached only a limited audience because of low performance or the need to install special viewers and Java libraries. Thanks to the broad support WebGL enjoys in browsers, for the first time, developers can now expect a larger user group.

Hardware Support

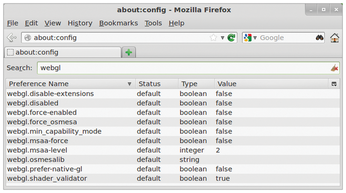

The easiest way to check the status of your computer is with the test page [3] of the WebGL consortium. If it shows no support in Firefox, it is a good idea to compare the settings under about:config with Figure 1. Chrome is somewhat picky concerning graphic cards. If WebGL support does not work immediately, it can be set manually in the configuration file /usr/share/applications/google-chrome.desktop with the line:

Exec=/opt/google/chrome/google-chrome --enable-webgl -ignore-gpu-blacklist %U

Details about graphic cards can be called up in Chrome with the chrome://gpu URL.

Programming with OpenGL was never a walk in the park, and WebGL is not so different. Unlike C or Java, compilation is not necessary with JavaScript, but with this low-level library, a lot of code still must be written before first results can be achieved. The solution is a library that encapsulates common tasks, such as creating basic geometric shapes or loading models or textures. This extra user friendliness is provided by the JavaScript library Three.js [4].

Three.js originates from a Spanish programmer who calls himself "Mr. Doob," and it is available under the MIT License. An overview of Three.js possibilities can be found in the extensive set of demos on the project website: From simple cubes to complex 3D scenes to vertex and fragment shaders. Further examples can be found in Jerome Etienne's blog [5] and on the page "Learning WebGL" [6]. These examples silence the frequently heard concerns about performance. Although JavaScript cannot compete with the performance of C++ or Java, as soon as the data has been loaded into the OpenGL stack, it hardly plays a role anymore.

WebGL also cannot yet achieve the performance levels of C++ [7] or Java applications [8] with their decades of maintenance, WebGL can create worlds with several hundred thousand polygons and run on multiple platforms without any extra installations.

No matter how intricate the scenes are, all Three.js programs run through the same steps:

- Load the JavaScript libraries

- Create the canvas

- Create the Three.js scene

- Start the event loops

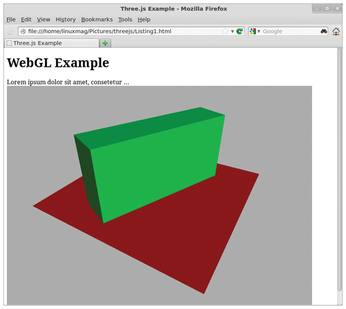

A simple example of this process is found in Listing 1, which generates the web page shown in Figure 2. The example uses the Three.js main library, as well as the Detector.js helper class. The HTML page integrates the libraries with the script tag in the header. Lines 16 and 17 use an absolute URL, but libraries that are available on your own server can also be retrieved over a relative path, such as js/Three.js. In contrast to plugins and applets, the area drawn by Three.js is not a foreign object in the website – the browser treats it as part of the normal HTML.

Listing 1

A Simple Example of Three.js

001 <!doctype html>

002 <html>

003 <head>

004 <title>Three.js Example</title>

005 <style type="text/css">

006 body {

007 background-color: #ffffff;

008 }

009

010 #ThreeJSCanvas {

011 background: #ababab;

012 width: 800px;

013 height: 600px;

014 }

015 </style>

016 <script src="https://github.com/mrdoob/three.js/raw/master/build/Three.js"></script>

017 <script src="https://github.com/mrdoob/three.js/raw/master/examples/js/Detector.js"></script>

018 </head>

019 <body>

020 <h1>WebGL Example</h1>

021 Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur ...

022

023 <div id="ThreeJSCanvas"></div>

024

025 <script>

026 var renderer;

027 var scene;

028 var camera;

029 var cameraControl;

030 var cubusMesh;

031

032 // Initialize the scene

033 init();

034

035 // Animate die scene

036 animate();

037

038 function init(){

039 console.log("init");

040

041 // If WebGL is supported by the browser, use the

042 // hardware-accelerated WebGL-renderer, otherwise the

043 // normal CanvasRenderer

044 if(Detector.webgl){

045 renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer({antialias:true});

046 } else {

047 renderer = new THREE.CanvasRenderer();

048 }

049

050 // Fetch the defined DIV element by its ID

051 var divElement = document.getElementById('ThreeJSCanvas');

052

053 // Set the renderer to the size of the DIV element,

054 var canvasWidth = divElement.offsetWidth;

055 var canvasHeight = divElement.offsetHeight;

056

057 renderer.setSize(canvasWidth, canvasHeight);

058

059 // and attach it to the DIV element

060 divElement.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

061

062 // Create the scene into which all objects will be inserted

063 scene = new THREE.Scene();

064

065 // Create the camera, set its position,

066 // and point it at the origin

067 camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(50, canvasWidth / canvasHeight, 1, 10000);

068 camera.position.set(3, 4, 5);

069 camera.lookAt( new THREE.Vector3( 0, 0,0));

070 scene.add(camera);

071

072 // Control of the camera with the mouse

073 cameraControl = new THREE.TrackballControls(camera, renderer.domElement);

074

075 // Define and insert a light source

076 var directionalLight = new THREE.DirectionalLight(0xffffff, 1.0);

077 directionalLight.position = new THREE.Vector3( 20,20,20);

078 scene.add(directionalLight);

079

080 // A 5X5-sized plane

081 var planeGeo = new THREE.PlaneGeometry(5, 5, 20, 20);

082 var planeMat = new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({color: 0xef0000});

083 var mesh = new THREE.Mesh(planeGeo, planeMat);

084 mesh.doubleSided = true

085 scene.add(mesh);

086

087 // A cube

088 var cubusGeo = new THREE.CubeGeometry( 1, 2, 4, 1,2,4); //new Three.new THREE.TorusGeometry( 1, 0.42 );

089 var cubusMat = new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial( { color: 0x00ef00 } );

090 cubusMesh = new THREE.Mesh( cubusGeo, cubusMat);

091 cubusMesh.position = new THREE.Vector3( 0, 1.01, 0);

092

093 scene.add( cubusMesh );

094

095

096 }

097

098 function animate(){

099

100 // Rotate the cube

101 cubusMesh.rotation.y = 1e-4* new Date().getTime();

102 // Rotating the camera according to user input

103 cameraControl.update();

104

105 // Rendering the scene

106 renderer.render(scene, camera);

107

108 // Next rendering only if required

109 requestAnimationFrame(animate);

110 }

111

112 </script>

113 </body>

114 </html>

The implementation of the example takes place in the JavaScript block starting in line 25. It calls up each function in turn to initialize the scene and start the event loop. The init function first uses the Detector.js helper library, which checks to see whether the browser supports WebGL and displays the result with the webgl attribute. If this is the case, the script can use the hardware-accelerated WebGL renderer; otherwise, it generates the CanvasRenderer. This will work on browsers without WebGL, but offers much fewer features.

Next, it is necessary to connect the renderer with the HTML element. Line 51 queries the div element using the ID from the Document Object Model (DOM). The following lines determine the size of the element and transfer it to the renderer. In line 60, the script inserts the DOM element from the renderer into the div element. Thus, the 3D part is embedded in the HTML page. Next, the 3D scene, represented by a Three.Scene object, needs to be defined. It serves as a parent node for the geometry to be portrayed as well as for the camera and lights.

Lights, Camera, Action!

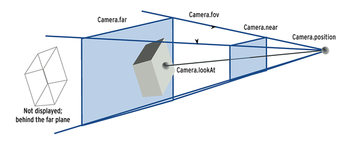

First the code first sets up the camera (from line 67). Three.js provides three camera classes: one with perspective projection (PerspectiveCamera), one with orthogonal projection (OrthographicCamera), and one that can switch between the two (CombinedCamera ). When creating the camera, programmers specify the field of view (fov), the aspect ratio, and the minimum (near) and maximum (far) distances to the geometrical figure. They thus define the viewing frustum, which is the pyramid-shaped volume defining the visible objects of the scene rendered on-- by the browser. Figure 3 shows the frustum with the corresponding Three.js parameters. An example [9] on the project site demonstrates some of these values.

Figure 3: The frustum determines the visible part of the 3D world. The properties of this viewing pyramid are defined by JavaScript variables in Three.js.

Figure 3: The frustum determines the visible part of the 3D world. The properties of this viewing pyramid are defined by JavaScript variables in Three.js.

In many cases, the programmer will want the user to control the camera position and direction. For this, Three.js provides ready-made solutions, such as the TrackballControls() in line 73. This control solution exhibits usual behavioral characteristics: The camera rotates when the left mouse button is pressed, zooms when the middle button is held, and moves with the right mouse button pressed. Additional controls, such as FirstPersonControl(), which walks through a scene, as in a first-person shooter, are available or can be programmed.

A camera is of little use in the dark, therefore the code defines the light source starting in line 76 and assigns it to a position. It radiates white light (0xffffff) with full intensity (1.0). In the example, the light source has a fixed position in the scene.

Now the only thing missing is the 3D world itself. Listing 1 generates a plane from line 81 and a cube from line 88 with JavaScript. For each object, code first defines the geometry and then generates the surface with a material (Mesh). Like the camera, the mesh is positioned and mounted in the scene.

The material determines the appearance of the object: In addition to simple colors, developers can use textures or shaders for the surfaces. Now, the definition of the 3D world is complete, and the event loop can be started.

Within the event loop, the code processes user input at regular intervals or animates the scene before a new image is rendered from the 3D scene. The animate() function is responsible for this in the example – for the first time in line 36 after the scene has been defined. So that a single call can become a real event loop, the requestAnimationFrame() function is used. It is managed by the browser and is responsible for regularly calling up the animate() function. It will also interrupt the event loop – for example, if the window is not currently visible – thereby saving system resources.

Previously, we saw how Listing 1 rotated the cube around its y-axis and then updated the camera position according to user input. Even if they appear similar at first glance, these are two distinct movements: The first action rotates the object in the scene, and the second action moves the perspective onto the scene. After the 3D scene has been updated accordingly, line 106 calls the renderer to integrate it into a 2D view.

Just planes and cubes would be somewhat boring, but Three.js provides even more options for generating 3D scenes. For example, it can generate geometric primitives (triangles, cubes, cylinders, spheres, lines) and extrude planes to create solids. The library can also load externally defined geometric figures and have the graphics card calculate vertex shaders. The ability to load external geometric figures makes Three.js particularly attractive for many applications because it allows integration of powerful modeling tools, such as Blender or a CAD system. Depending on the application, this can be done either with the Three.js loader for external formats, such as Wavefront Object, Collada, and VTK, or with a converter that translates files into the JSON format of Three.js. This ASCII file defines the points, planes, normals, and colors. Even animated models, such as walking people, can be stored in such files.

Importing Geometries

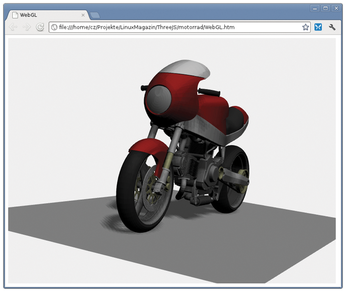

Converters for the command line, as well as plugins for Blender and 3DS Max, are found under utils/exporters in the Three.js source code. More converters can be programmed relatively quickly: Using a self-written converter, the authors exported the motorcycle in Figure 4 to JSON from the JT format common in the CAD world. Listing 2 loads JSON files. The load() function requires both the URL of the JSON file and a callback function for further actions after loading. This function defines the material, creates a mesh, and adds it to the scene, as was done with the manually created geometry in Listing 1.

Listing 2

Load JSON data

01 var loader = new THREE.JSONLoader();

02 loader.load("mini.json", function(geometry){

03 var material = new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial( { color: 0x00efef } );

04

05 mesh = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

06

07 mesh.doubleSided = true;

08 THREE.GeometryUtils.center(geometry);

09 scene.add(mesh);

10 });

The mesh attribute doubleSided deactivates back-face culling, so that both sides of a surface are shown. Without this parameter, only the side with a normal vector facing the camera would be rendered. If the normal vectors are not uniform, it can result in holes in the surface.

GeometryUtils moves the geometry to the pole; otherwise, it would be positioned at its original location and might not be visible after loading.

When loading external geometries, the normal security mechanisms of the browser are applied. Chrome, for example, will only allow it if the HTML page and the JSON data come from the same server. Loading directly from the local hard drive is only possible if Chrome has been started with the -disable-web-security option.

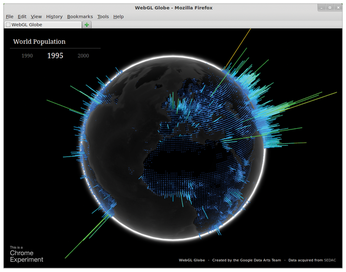

In this article, we have only scratched the surface of what the versatile Three.js is capable of doing: Besides explicitly generated or imported geometry, the library also supports visualization techniques such as sprites and includes a particle system. Beyond that, geometries and colors can be defined down to the last detail with vertex and fragment shaders [10]. Applications with data visualizations [11] (Figure 5) or the game "Zombies vs Cow" [12] (Figure 6) demonstrate the possibilities.

Many exciting developments will take place in future implementations of WebGL in browsers, in further development of Three.js, and in the world of converters – for example, in games with physics engines such as Physijs [13] and in CAD with CSG (Constructive Solid Geometry) libraries that use Boolean operators to combine geometric primitives [14].

Development will be aided by common JavaScript utilities like dat-gui [15] or consoles in Firefox and Chrome. The WebGL Inspector [16] allows a look deep into the OpenGL stack. Alternatively, complete 3D scenes can be defined via drag and drop with ThreeNodes.js [17].

Even now, getting started with 3D programming is easier with Three.js than with almost any other technology. Browsers capable of WebGL are already widespread, and will continue to increase, on both desktop and mobile devices. The combination of 2D and 3D in particular will give rise to an increasing number of new applications that will go far beyond the demo scene or amusing games. For example, the authors of this article are working on a viewer called CADOculus that renders CAD data in web browsers [18].

Infos

- "HTML 5" by Peter Kreußel, Linux Magazine, October 2010, pg. 34

- WebGL: http://www.khronos.org/webgl/

- WebGL test: http://get.webgl.org

- Three.js project: https://github.com/mrdoob/three.js/

- Learning Three.js: http://learningthreejs.com

- Learning WebGL: http://learningwebgl.com/blog/

- OpenSceneGraph: http://www.openscenegraph.org

- jMonkeyEngine: http://jmonkeyengine.com

- Frustum: http://mrdoob.github.com/three.js/examples/webgl_camera.html

- Shader tutorial: http://aerotwist.com/tutorials/an-introduction-to-shaders-part-1/

- Visualization of world population growth: http://data-arts.appspot.com/globe

- Zombies vs Cow: http://yagiz.me/zombiesvscow/

- Physijs: http://chandlerprall.github.com/Physijs/

- CSG: http://evanw.github.com/csg.js/

- dat-gui: http://code.google.com/p/dat-gui/

- WebGL Inspector: http://benvanik.github.com/WebGL-Inspector/

- ThreeNodes.js: http://idflood.github.com/ThreeNodes.js

- CADOculus: http://www.cadoculus.de (in German)

- Listings for this article: http://www.linuxpromagazine.com/Resources/Article-Code

Buy this article as PDF

(incl. VAT)

Buy Linux Magazine

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Introducing matrixOS, an Immutable Gentoo-Based Linux Distro

It was only a matter of time before a developer decided one of the most challenging Linux distributions needed to be immutable.

-

Chaos Comes to KDE in KaOS

KaOS devs are making a major change to the distribution, and it all comes down to one system.

-

New Linux Botnet Discovered

The SSHStalker botnet uses IRC C2 to control systems via legacy Linux kernel exploits.

-

The Next Linux Kernel Turns 7.0

Linus Torvalds has announced that after Linux kernel 6.19, we'll finally reach the 7.0 iteration stage.

-

Linux From Scratch Drops SysVinit Support

LFS will no longer support SysVinit.

-

LibreOffice 26.2 Now Available

With new features, improvements, and bug fixes, LibreOffice 26.2 delivers a modern, polished office suite without compromise.

-

Linux Kernel Project Releases Project Continuity Document

What happens to Linux when there's no Linus? It's a question many of us have asked over the years, and it seems it's also on the minds of the Linux kernel project.

-

Mecha Systems Introduces Linux Handheld

Mecha Systems has revealed its Mecha Comet, a new handheld computer powered by – you guessed it – Linux.

-

MX Linux 25.1 Features Dual Init System ISO

The latest release of MX Linux caters to lovers of two different init systems and even offers instructions on how to transition.

-

Photoshop on Linux?

A developer has patched Wine so that it'll run specific versions of Photoshop that depend on Adobe Creative Cloud.