The League of Moveable Type

Open Source Fonts

ByThe Free Font Movement is transforming free software, one character at a time.

Fonts were a late concern on the free desktop. As late as 2004, free fonts were almost non-existent, and the few that existed were of low quality. Yet a decade later, hundreds of free-license fonts are available on sites like Google Fonts and the Open Font Library. However, no site is known for quality more than The League of Moveable Type, a site dedicated to promoting free fonts and educating users about typography.

Billing itself as “the first free font foundry,” The League of Moveable Type was founded in 2009 by Micah Rich as a spinoff from the A Good Company design studio. Rich’s education was in motion graphics and graphic design, so he describes his education in typography as “pretty practical and traditional.” However, he adds, “I was interested in the web, too, and ended up using my senior thesis to teach myself more than just web design. I got into Ruby and Rails and a handful of other tools, and the community in those things are so open and sharing. My programming background has really influenced how I think about things.”

At the time, the standard wisdom was that typographers considered themselves artists and would never give their work away, nor let others expand upon it. Although the situation is quickly improving, even today, Rich says, “The typography industry is built on a whole lot of history, and the professional type designers often pride themselves on their similarities to antique processes and ideals.” In fact, “the type industry is just barely starting to come into the new millennium. More established type designers are just now starting to see the benefits of the digital world.”

Contrary to the prevailing wisdom, Rich also maintains that people are becoming more willing to release the code for their design. For one thing, he suggests, it is good marketing – “from a business standpoint, giving away good stuff for free makes people feel like the stuff they can pay for must be even better.”

More importantly, Rich observes: “I feel like we’re almost all changing our brains a bit the more that we get used to the Internet being such a big part of out lives. We’re at this point where it almost makes sense to share stuff with people. I know a lot of people I’ve worked with don’t even think too hard about why they want to share – they just feel weird about not sharing. It doesn’t come with a huge sense of nobility, either; it’s more like practicality.”

The Birth of a Foundry

By 2009, the idea of sharing fonts was becoming acceptable, at least in some circles. In 2006, designer Victor Gaultney had released the code for his award-winning Gentium, one of the first original high-quality designs for a free font. A year later, a revision of the SIL Open Font License had specifically reserved font names so that designers could retain credit for their work and outlawed selling fonts released under it without software in the hopes of preventing knockoff collections. At the same time, the license specifically permitted embedding fonts in other works.

Although both Debian and the Free Software Foundation initially questioned some of these provisions, the SIL OFL quickly became accepted as a free license. It seemed to be what designers were waiting for, because in the years since, it has become the license of choice for most free fonts.

Rich remembers the exact moment when The League was born. A Good Company was looking for fonts for a project, and Rich saw a student on a forum who asked where he could find free fonts receiving angry answers from professionals who felt he was undermining their livelihood. “I’d spent so much time in the open source programming world that it just shocked me,” Rich recalls, “and I wanted to cause a ruckus, to show them it could be done, and it could be a good thing. So we did it.”

The League soon became a showcase for high-quality free fonts. Asked what criteria are used to judge fonts, Rich admits that, “As much as we’ve tried to come up with processes for quality, it’s still 80 percent subjective. We’re all designers, and we’ve got enough experience using fonts to know which ones work well and look good.”

All the same, over the years, “basic requirements have grown into place, mostly centered around double-checking line quality, file integrity, character maps, kerning, and measurements. [But] the truth is, we don’t even get that far until we’ve agreed that people will like something. I suppose [it] boils down to experience and gut.”

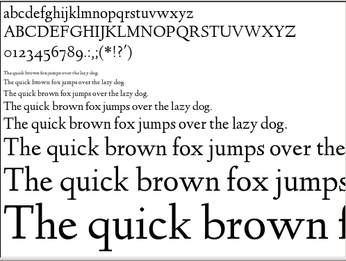

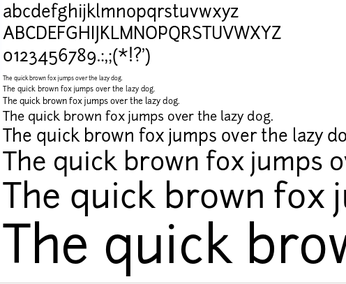

Rich’s own preference is “for reviving old typefaces that people have forgotten about or finding ways to make our own take on fonts people already love but don’t have open source versions for.” For example, the League promotes three fonts by designer Barry Schwartz that are revivals of the work of Frederick Goudy: Sorts Mill Goudy, based on Goudy Oldstyle, the design that Goudy is best known for today, as well as Goudy Bookletter 1911, based on Goudy’s Kennerley Oldstyle, and Linden Hill, based on Goudy’s Deepdene. By contrast, Schwartz’s Fanwood is a near replacement for Eric Gill’s Joanna, which is available commercially from Adobe.

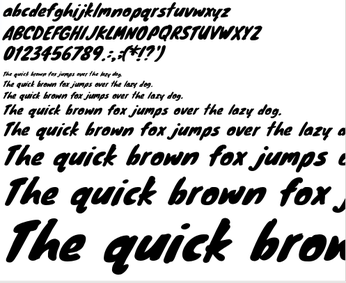

Still other League fonts are original designs, such as Junction, its first project, and Matt McInerney’s Raleway. A few, like Knewave, are display fonts suitable for brochures or posters, but the majority are reliable fonts suitable for large passages of text – the sort you would use to design a book.

The League site is also dedicated to educating users, with a newsletter, blog posts, and a few small books about how to use free fonts, all of which are written by Rich. More privately, the League members also occasionally take commissions. “Mostly,” Rich says, “its that a larger company wants to expand a typeface we’ve started and use it for their branding or a project. On those occasions, we get paid to work on making great fonts, and clients are benefiting from our expertise.

What’s Next

Rich admits that he is somewhat taken aback from the growing tendency of free software projects to include fonts as part of their branding, such as Gnome’s Cantarell or KDE’s Oxygen. “I probably shouldn’t admit it,” he said, “But I often struggle to see the necessity of a completely custom font in branding.” However, at the same time, he sees the tendency as an “awesome” example of how the free font movement is gaining momentum.

“It’s just getting started,” Rich says. “The first few years were slowly percolating, expanding the idea out little by little. We started with no one, and we’ve built up a handful of great designers and people who support it, and we’ve slowly build a decent following of people who care about it.”

Rich continues: “That slow start, from the bottom up, has changed culture more than it seems – we started when browsers were just barely talking about supporting rendering custom fonts in web pages. Now, you almost can’t imagine seeing a site without it. I don’t think it’s too self-indulgent to say the League had a decent part in helping get there.”

All the same, Rich would like to see more. He considers the efforts to educate as no more than the “beginnings” of encouraging people to try font design. “But I want to expand that. We have the opportunity and ability to start really building a community of type designers who value the same things we do, the same things the modern programming communities do, but it means doing more to educate, in more ways, and that means getting people on our side who love the craft, and understand the craft, and can teach it.”

Today, there are no more than 100 free fonts for every 1,000 proprietary ones. However, thanks to designers like the members of The League of Moveable Type, at least designers have a choice of working with free fonts without having to sacrifice quality. Better yet, every sign indicates that the future will be even better.

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Chaos Comes to KDE in KaOS

KaOS devs are making a major change to the distribution, and it all comes down to one system.

-

New Linux Botnet Discovered

The SSHStalker botnet uses IRC C2 to control systems via legacy Linux kernel exploits.

-

The Next Linux Kernel Turns 7.0

Linus Torvalds has announced that after Linux kernel 6.19, we'll finally reach the 7.0 iteration stage.

-

Linux From Scratch Drops SysVinit Support

LFS will no longer support SysVinit.

-

LibreOffice 26.2 Now Available

With new features, improvements, and bug fixes, LibreOffice 26.2 delivers a modern, polished office suite without compromise.

-

Linux Kernel Project Releases Project Continuity Document

What happens to Linux when there's no Linus? It's a question many of us have asked over the years, and it seems it's also on the minds of the Linux kernel project.

-

Mecha Systems Introduces Linux Handheld

Mecha Systems has revealed its Mecha Comet, a new handheld computer powered by – you guessed it – Linux.

-

MX Linux 25.1 Features Dual Init System ISO

The latest release of MX Linux caters to lovers of two different init systems and even offers instructions on how to transition.

-

Photoshop on Linux?

A developer has patched Wine so that it'll run specific versions of Photoshop that depend on Adobe Creative Cloud.

-

Linux Mint 22.3 Now Available with New Tools

Linux Mint 22.3 has been released with a pair of new tools for system admins and some pretty cool new features.