Reverse engineering a BLE clock

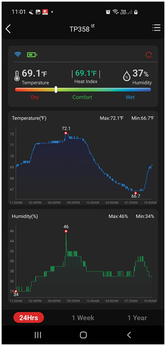

A while ago, I bought a ThermoPro TP358, a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) digital thermometer with a display. The ThermoPro shows the temperature, humidity, and air comfort indicator, as well as the time and day of the week. Its big display is nice for immediate feedback, but the device also lets you read its values and view graphs in the ThermoPro Sensor app, available on Android and iOS (Figure 1). Moreover, every time you connect to the device with the app, it synchronizes the time.

Figure 1: The ThermoPro Sensor app synchronizes the time of the digital thermometer upon connection.

Figure 1: The ThermoPro Sensor app synchronizes the time of the digital thermometer upon connection.

While that is a nice feature, I have a couple of other types of Bluetooth sensors with a clock, and I didn't want to use multiple apps to view the sensor measurements and synchronize the clocks. For the sensor measurements, a solution already exists: Software such as Home Assistant [1] supported my devices out-of-the-box, letting me view their measurements in Home Assistant's dashboard. However, I couldn't find any solution that let me synchronize the time across all of my Bluetooth clocks without using the individual apps.

[...]

Buy this article as PDF

(incl. VAT)

Buy Linux Magazine

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Parrot OS Switches to KDE Plasma Desktop

Yet another distro is making the move to the KDE Plasma desktop.

-

TUXEDO Announces Gemini 17

TUXEDO Computers has released the fourth generation of its Gemini laptop with plenty of updates.

-

Two New Distros Adopt Enlightenment

MX Moksha and AV Linux 25 join ranks with Bodhi Linux and embrace the Enlightenment desktop.

-

Solus Linux 4.8 Removes Python 2

Solus Linux 4.8 has been released with the latest Linux kernel, updated desktops, and a key removal.

-

Zorin OS 18 Hits over a Million Downloads

If you doubt Linux isn't gaining popularity, you only have to look at Zorin OS's download numbers.

-

TUXEDO Computers Scraps Snapdragon X1E-Based Laptop

Due to issues with a Snapdragon CPU, TUXEDO Computers has cancelled its plans to release a laptop based on this elite hardware.

-

Debian Unleashes Debian Libre Live

Debian Libre Live keeps your machine free of proprietary software.

-

Valve Announces Pending Release of Steam Machine

Shout it to the heavens: Steam Machine, powered by Linux, is set to arrive in 2026.

-

Happy Birthday, ADMIN Magazine!

ADMIN is celebrating its 15th anniversary with issue #90.

-

Another Linux Malware Discovered

Russian hackers use Hyper-V to hide malware within Linux virtual machines.