Anonymous: Activist Hackers in the Headlines

By

The Anonymous Hacktivist group has been in many headlines this past year. Who are they? What did they attack? How do they communicate?

As we put the final touches on this article, operation Megaupload, #OpMegaupload, is in full force (Figure 1).

The hacktivist group Anonymous has claimed responsibility for a coordinated attack on the websites of the Justice Department, the Motion Picture Association of America, the Recording Industry Association of America, and Universal Music. They used their weapon of choice: the Low-Orbit Ion Cannon (LOIC) to carry on distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks on these sites. According to the chatter on IRC and Twitter, these attacks were carried out in retaliation for the takedown of the popular site Megaupload by US and New Zealand authorities on charges of copyright infringement, racketeering, and money laundering (Figure 2). One of the chief Megaupload executives, Kim Dotcom, has since been denied bail in New Zealand.

An Internet blackout also occurred the same week, and a reported 75,000 websites went dark, including Wikipedia, in a protest against the anti-piracy bills SOPA and PIPA in the US Congress. In view of all the protest, Congress postponed the bills and is going back to the drawing board. The timing could not have been better or worse, depending how you look at it; the actions of Anonymous could harm more than help the cause of net neutrality.

Who Are They?

If you’ve heard about Anonymous on the news, you have seen the Guy Fawkes masks and the YouTube videos portraying alleged Anonymous members taking responsibility for an attack or warning a company of an impending one. You might also have read their rather eerie mantra, “We are Anonymous. We are Legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget. Expect us.” Their actions have made quite a few headlines in the last couple of years, ranging from protests against the Church of Scientology, to a fight against the Mexican cartels, to, more recently, a break-in of Stratfor Global Intelligence servers, from which they accessed 2.7 million email accounts and some credit card numbers, which have been used to make charitable donations. Although Anonymous is becoming increasingly synonymous with a hacker group committing crimes, there is more to it.

Anonymous in its larger definition is a social activism group empowered by social media sites like Twitter and Facebook. They represent a new type of activism – leaderless, unorganized, rooted in the Internet – with the ability to mobilize a large number of people quickly around a specific issue. The four top Anonymous-related Twitter accounts (@anonops, @AnonymousIRC, @Anonymous, @Lulzsec) have more than 800,000 followers, giving them significant clout. YouTube videos about or from Anonymous get millions of views. During the DDoS attacks on the Justice Department, LOIC saw a large increase in its number of downloads, peaking around 50,000 in a week. Anonymous reported that 5,630 members participated in the attack.

A Guy Fawkes mask (Figure 3) is a stylized depiction of the most famous member of the Gunpowder plot that aimed to bomb the British parliament on November 5, 1605. It was made famous by the comic book and movie "V for Vendetta" in 2005. Although its meaning has evolved over the years, it has been embraced by Anonymous has a symbol of protest.

A Short History of Anonymous

Although most social activism groups have a clear structure and well-defined communication channels, that is not the case for Anonymous, perhaps the first virtual social activism group. In the beginning, members might have used a site like 4chan, which allows anonymous posts, but they now use various IRC channels, primarily on the server irc.anonops.com. Most of the talk is about random topics ranging from computer games to programming and occasionally current events. This has always been the case for Anonymous and is the core of Anonymous at large.

Anonymous became more than various people chatting anonymously when they realized they could do things outside of the IRC channels. The first acts were relatively childish and motivated by entertainment and for lulz. For example, when Dumbledore died in the the newest Harry Potter book, someone likely spoiled the ending for everyone in the chat room. The news spread to the point that the ending was spoiled for everyone in what seemed like a coordinated action by Anonymous. With the history of simple pranks for entertainment and fame, Anonymous grew used to looking for things to do as a collective in the real world.

Eventually, operations shifted toward activism. Core discussions still take place on IRC channels, although not all focused on activism. As ideas come up, most are ignored, but the most interesting ones gain support. No one votes on what they should or should not do, but if someone likes an idea, they might tweet about it, post it on Facebook, make a YouTube video, or mention it on a blog, thus lending their support and helping make it a reality. In turn, more people find out about the idea and try to contribute to the goal in whatever way they can. From an idea in an IRC channel to real action, growth is purely organic and generates an eventual consensus on the operation at large, although not on the specifics of the operation.

In a sense, the decision about what to do is made by actually doing it. Generally, each operation has an overall target, and any actions taken are at an individual’s discretion, which leaves a wide range of interpretations about how the operation can be carried out. Sometimes coordinated actions, like protests, gain support, and a group manages to agree on dates and a place. The occupy movement, for instance, received support from Anonymous, and the Guy Fawkes mask could be seen among the protesters. More computer savvy individuals might decide to hack websites in support of an operation, thereby engaging in criminal activities. So even though a consensus might be reached on the operation, not all members of Anonymous agree on individual deeds that could include criminal acts. This has lead to the current portrayal of Anonymous solely as a hacker’s group, attacking corporations and stealing information and could lead to the demise of true social activism being associated with the group.

Anonymous as a Hacktivist Group

What has really put Anonymous in the spotlight are hacking groups like Lulz Security. Privacy and Internet freedom are core values for both Anonymous and most hacktivist groups, so these hacking groups will sometimes take advantage of the Anonymous leaderless and open membership structure to contribute their actions as part of Anonymous operations. Anonymous' name recognition and its pure number of followers and members mean that the actions hacktivists take part in will likely receive more attention if they partner with Anonymous than if they just do something on their own. A few attacks that received significant press attention were relatively simple, mostly based on LOIC. However, more involved attacks, such as website defacing and, more recently, access to servers, show that some members of Anonymous are extremely skilled hackers. During #OpNewBlood, an alleged Anonymous Super Security Handbook was released that explains in detail how to remain anonymous on the Internet. As such, it is a good anonymity handbook. It covers the use of IRC, proxies, multiple Firefox add-ons to disable usage tracking, and HTTPS everywhere, and it introduces more involved anonymity services such as Tor and I2P2. In the rest of the article, I describe a few key computer attacks carried out under the Anonymous identity.

Project Chanology

This attack was initiated on January 15, 2008, from one of the 4chan message boards. It started out as a DDoS attack on www.scientology.org using the site gigaloader.com. Gigaloader allowed people to paste links to images for a target website. It would constantly reload those images and in turn would quickly use up a website’s bandwidth. With as few as a hundred or more users sending the same requests, it had the potential to slow the website down to a crawl or render it totally unavailable. The Gigaloader site is no longer available. What is interesting about Project Chanology is that it feature multiple actions, such as physical protests, prank calls, and a YouTube video stating that Anonymous wanted to “expel the church from the Internet.” It shows how a combination of social activism and hacktivism merged in a single operation.

LOIC

The Low-Orbit Ion Cannon is a tool written in C# by a developer called praetox as a legitimate stress-testing application. It will send TCP, UDP, or HTTP requests to the target repeatedly. Of course, If enough clients are targeting the same site, this can lead to a DDoS. A newer version called IRC-LOIC added a “hivemind” feature that would allow it to be controlled from an outside host via IRC; this is basically volunteering to join a botnet that can be controlled via IRC to initiate an attack to a specific target. Yet a newer version of LOIC, called JS LOIC, runs from a website via JavaScript. This latest version was used in #OpMegaupload, ushering in a new type of attack – “Drive By DDoS” – in which people who followed a link posted on Twitter by members of Anonymous could unintentionally run the JavaScript LOIC targeted at the US Justice Department.

Operation Payback, #OpSony, and Avenge Assange

Beginning September 17, 2010, LOIC DDoS attacks were launched against the entertainment industry in retaliation for DDoS attacks ordered by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) against websites that did not respond to takedown notices. The initial target was Aiplex Software, the India-based company that was hired by the MPAA, but their site had already been brought down by someone else. Anonymous then moved to launching attacks against the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), and law firms that were involved in copyright infringing enforcement.

The second wave of this attack was named #OpSony and targeted Sony Entertainment. After George Hotz, alias geohot, jailbroke the PlayStation 3, Sony filed a lawsuit against him. Sony was also granted by a federal magistrate the right to acquire the IP addresses of anyone who had visited his website from January 2009 to March 2011. In return, Anonymous initiated DDoS attacks against numerous Sony websites.

In December 2010, Anonymous changed its focus to support WikiLeaks. DDoS attacks began against Amazon, PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and the Swiss Bank Post Finance because these financial institutions canceled services and funding to the WikiLeaks website and its members. The operation, called Avenge Assange, took down the Visa and MasterCard websites on December 8. After WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was arrested, refused bail in London, and threatened with extradition to Sweden for charges of rape and molestation, Anonymous launched an attack that brought down the Swedish prosecutor’s website.

#Ophbgary

One of the most publicized and documented attack by Anonymous was #Ophbgrary. In early 2011, Aaron Barr, CEO of HB Gary Federal, told the Financial Times that with the use of IRC timestamps and social networking websites he had penetrated Anonymous and was prepared to release his findings at the security B-Sides conference in San Francisco. Anonymous quickly compromised the company’s website, gained access to his research with the findings on its members, and published more than 60,000 of HBGary’s email messages.

Anonymous discovered a SQL injection vulnerability in the hbgaryfederal.com custom content management system (CMS). They were able to dump the usernames, email addresses, and password hashes for the CMS users. Although the passwords were hashed, two of the passwords were very weak; all lowercase letters, six characters in length, including two numbers. The two accounts whose passwords were compromised were Barr’s and the COO Ted Vera. Unfortunately for them, they failed to follow a security best practice of using a unique password for each application and system. This same password gave Anonymous access to their email, Twitter, and LinkedIn accounts. Using Vera’s account they were also able to authenticate to one of HBGary Federal’s support servers using SSH. Although his account had limited privileges, Anonymous was able to identify and exploit a privilege escalation vulnerability in the GNU C library dynamic linker that had been around since October 2010. On the server, they discovered gigabytes of backup and research data, which they promptly deleted. Barr’s account and password gave them administrative access to the company’s email via Google Apps

They used this to access the email of one of the company’s founders Greg Hoglund. Hoglund also founded and operates rootkit.com. Using the information found in Hoglund’s email and a little social engineering, Anonymous was able to gain root access to the hosting server for rootkit.com. Once the attack was over, Anonymous uploaded 60,000 pieces of company email on the BitTorrent network, defaced the HBGary Federal and rootkit.com websites, took over Barr’s Twitter account, which they used to tweet his home address and social security number, and posted the research data that Barr had been preparing to present during the security conference and discuss with the FBI.

Stratfor

Before #OpMegaupload, Anonymous had claimed responsibility for an attack that took place during Christmas. Strategic Forecasting Inc. (Stratfor), a geopolitical think tank was hacked. LOIC was not involved, similar to HBGary Anonymous gained access to the company server and released private information to the public. According to Anonymous’s unofficial spokesman Barrett Brown, Stratfor was targeted for their 2.7 million units of email, which included correspondence with thousands of clients who “work for major corporations within the intelligence and military contracting sectors, government agencies, and other institutions for which Anonymous and associated parties have developed an interest since February of 2011.” According to the Antisec Zine that was listed by the Twitter account @YourAnonNews, the initial attack vector appears to be Stratfor’s website, which was “vulnerable as hell.”

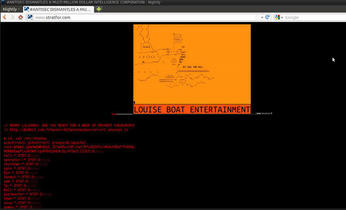

It is unknown how they gained root access, but once they did, they found the database credentials stored in the Drupal config file settings.php. In the database, they found a table full of Stratfor’s subscriber’s credit card numbers, expiration dates, and CVV numbers – all in cleartext. Using an account called “autobot,” which had SSH keys stored locally, they pivoted to other servers throughout Stratfor. On one server, they grabbed Stratfor’s mail spools from the Zimbra mail server. When they were done pillaging, they defaced the primary web server’s homepage (Figure 4) and wiped out its hard drive. In all, Anonymous claimed to have lifted millions of internal documents, 860,000 usernames and md5-hashed passwords, data from 75,000 credit cards, and more than 2.5 million email messages.

The Anonymous Zine also included an alleged hacklog for the Stratfor attack. This is a good source of information of any penetration tester out there because it gives good forensic data to protect your system. The hacklog doesn’t include how root access was obtained, and it starts out at the root command prompt on the primary server (www3):

www3 # unset HISTFILE www3 # id uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=81(apache) www3 # uname -a Linux www3 2.6.24-gentoo-r4 #1 SMP Mon Apr 14 16:06:51 CDT 2008 x86_64 Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5345 @ 2.33GHz GenuineIntel GNU/Linux www3 # cat /etc/shadow root $6$mG.Zpm0m$Wb6EqI.JE7wOPxc5XF/CwV/M7uQ0I6fxr4K9vh8DeFThXRGw.M0MbBGapP1vS 5mR/UydFBV52H14LGLreTGc0:15315:0::::: halt:*:9797:0::::: autobot: $6$CpUx69ju$yiq1B.LSe9R3Jxn3CEiPid5ZnBov.GSzgaiZU82iiVN1KEkipHtDQKsMZXjURPSRZp KpAx1GRXbO7gL4bSV61:14691:0:99999:7::: … www3 # w; ps -aux www3 # cat sites/default/settings.php <?php // $Id: default.settings.php,v 1.8.2.4 2009/09/14 12:59:18 goba Exp $ $base_domain = ‘<a href="http://www.stratfor.com/">www.stratfor.com</a>’; … www3 # mysql -u www -pVMRLNbWA6dL8JKqX -hdb2.stratfor.com mysql> select * from stratfor_billing_credit_card limit 70000, 100; +--------+--------------------- +------------------+------------------+-----------------+------+ | uid | name | number | expiration_month | expiration_year

Anonymous first hid their tracks with unset HISTFILE, then they gathered basic information with id, uname -a, ps -aux, and cat /etc/shadow. With this information, they began to enumerate each user’s .bash_history, .mysql_history, and .ssh files. One specific item was the public/private keypair for the autobot account, which they used to pivot to the “core” server.

Finally, to hide their tracks further, they pivoted with ssh autobot@sh.stratfor.com -T. The -T switch disables pseudo-tty allocation. This prevents the login from being reported with the last command to show a listing of the last logged-in users. It also prevents the commands from being written to history because it’s considered a non-interactive shell, although the login would still be logged if the system is configured to do so.

Conclusion

With the anatomy of the attack on Stratfor, we are now far removed from a Harry Potter prank and way above the fairly straightforward use of LOIC by script kiddies or even non-computer savvy supporters. Anonymous has demonstrated the ability to mobilize a large number of supporters and carry out operations on and off the Internet. Although some of their operations might have some legitimacy in the exercise of democracy, the recent attacks are crimes. Anonymous can disrupt traffic with basic DDoS but also gain access and steal information. From that perspective, Anonymous could be considered akin to a computer militia used in cybersecurity attacks. However, it is easy to equate the entirety of Anonymous with the group of criminals attacking organizations. The question is, will social activism survive the Hacktivists?

The Authors

Sebastien Goasguen is an Associate Professor at Clemson University, where he teaches distributed computing and network security. John Hoyt is a certified penetration tester and CISSP professional working at Clemson University as a security engineer. Ryan Cooke is a graduate student in Computer Science at Clemson University.

next page » 1 2 3 4 5

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Mecha Systems Introduces Linux Handheld

Mecha Systems has revealed its Mecha Comet, a new handheld computer powered by – you guessed it – Linux.

-

MX Linux 25.1 Features Dual Init System ISO

The latest release of MX Linux caters to lovers of two different init systems and even offers instructions on how to transition.

-

Photoshop on Linux?

A developer has patched Wine so that it'll run specific versions of Photoshop that depend on Adobe Creative Cloud.

-

Linux Mint 22.3 Now Available with New Tools

Linux Mint 22.3 has been released with a pair of new tools for system admins and some pretty cool new features.

-

New Linux Malware Targets Cloud-Based Linux Installations

VoidLink, a new Linux malware, should be of real concern because of its stealth and customization.

-

Say Goodbye to Middle-Mouse Paste

Both Gnome and Firefox have proposed getting rid of a long-time favorite Linux feature.

-

Manjaro 26.0 Primary Desktop Environments Default to Wayland

If you want to stick with X.Org, you'll be limited to the desktop environments you can choose.

-

Mozilla Plans to AI-ify Firefox

With a new CEO in control, Mozilla is doubling down on a strategy of trust, all the while leaning into AI.

-

Gnome Says No to AI-Generated Extensions

If you're a developer wanting to create a new Gnome extension, you'd best set aside that AI code generator, because the extension team will have none of that.

-

Parrot OS Switches to KDE Plasma Desktop

Yet another distro is making the move to the KDE Plasma desktop.