Using Git hooks to check your commit code

Secure Commitment

© Photo by Rawpixel on Unsplash

The pre-commit framework lets you automatically manage and maintain your Git hook scripts to deliver better Git commits.

When developing software in a public Git [1] repository, it's recommended to check for common issues in your code prior to committing your changes. Neglecting to do so could lead to your Git repository being cluttered with commits that just fix some minor syntax or style issue. To err is human. Consequently, relying solely on manual checks isn't enough to deliver quality code.

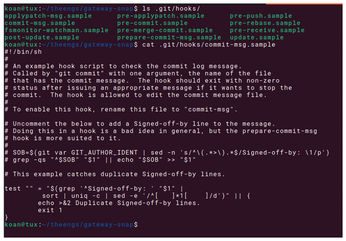

To address this issue, the Git version control system offers a way to start custom scripts when specific actions occur, such as committing changes or merging branches: Git hooks [2]. These hooks are executable (often shell) scripts, stored in the .git/hooks directory of a Git repository. When you create a new repository with the git init command, this directory is populated with several example scripts (Figure 1). Removing the .sample extension from a file name is all that's necessary to enable this hook.

[...]

Buy this article as PDF

(incl. VAT)

Buy Linux Magazine

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Nitrux 6.0 Now Ready to Rock Your World

The latest iteration of the Debian-based distribution includes all kinds of newness.

-

Linux Foundation Reports that Open Source Delivers Better ROI

In a report that may surprise no one in the Linux community, the Linux Foundation found that businesses are finding a 5X return on investment with open source software.

-

Keep Android Open

Google has announced that, soon, anyone looking to develop Android apps will have to first register centrally with Google.

-

Kernel 7.0 Now in Testing

Linus Torvalds has announced the first Release Candidate (RC) for the 7.x kernel is available for those who want to test it.

-

Introducing matrixOS, an Immutable Gentoo-Based Linux Distro

It was only a matter of time before a developer decided one of the most challenging Linux distributions needed to be immutable.

-

Chaos Comes to KDE in KaOS

KaOS devs are making a major change to the distribution, and it all comes down to one system.

-

New Linux Botnet Discovered

The SSHStalker botnet uses IRC C2 to control systems via legacy Linux kernel exploits.

-

The Next Linux Kernel Turns 7.0

Linus Torvalds has announced that after Linux kernel 6.19, we'll finally reach the 7.0 iteration stage.

-

Linux From Scratch Drops SysVinit Support

LFS will no longer support SysVinit.

-

LibreOffice 26.2 Now Available

With new features, improvements, and bug fixes, LibreOffice 26.2 delivers a modern, polished office suite without compromise.