The Latest Challenge to Copyleft

Copilot

ByGitHub's Copilot takes code autocompletion to a new level but raises copyleft licensing issues.

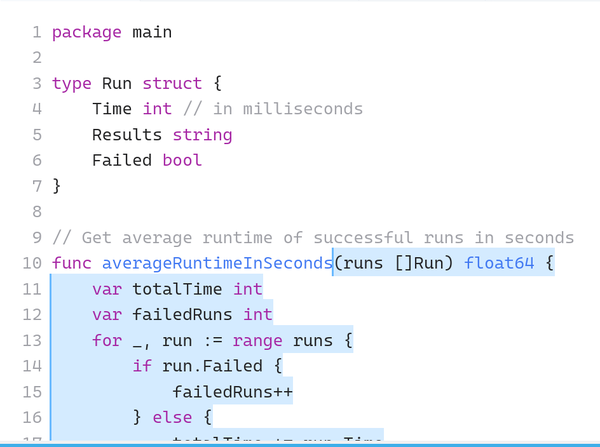

In a world where most people carry a cell phone, autocomplete might seem too widely used to cause contention. However, Copilot, a new code autocompletion service for Visual Studio Code (Figure 1), is already raising licensing issues, especially for copyleft licenses like the different versions of the GNU General Public License (GPL) that are the backbone of free software.

Code assistants are not new. However, Copilot claims to be in a class of its own. Developed by GitHub, Copilot is built on Codex, the new AI system created by OpenAI, and trained with all the public code on GitHub in dozens of programming languages. With this backing, Copilot includes the potential to reduce the time coders take to write or find examples or to learn a new programming language. It also makes possible innovative features like the conversion of code descriptions in comments to code, autofill for repetitive code, suggestions for code tests, and lists of alternatives, taking autocompletion to entirely new levels.

However, along with these completions comes new licensing problems. Copilot’s developers quibble that it is a code synthesizer, not a search engine, and insist that “the vast majority of the code that it suggests is uniquely generated and has never been seen before. We found that about 0.1% of the time, the suggestion may contain some snippets that are verbatim from the training set.… Many of these cases happen when you don’t provide sufficient context (in particular, when editing an empty file), or when there is a common, perhaps even universal, solution to the problem. We are building an origin tracker to help detect the rare instances of code that is repeated from the training set, to help you make good real-time decisions.” In other words, exact copying is rare, usually the user’s fault, and should be detectable in the future.

Meanwhile, and perhaps even after an origin tracker is included, the possibility remains for unintentional copyright violations. For example, public domain code may still have copyright restrictions. If you borrow public domain code with restrictions, have you violated copyright?

The potential for violations is even stronger with copyleft, which is likely to be common in the code used for training. How much code, if any, can be copied from an application released under a version of the GPL? Does borrowing via Copilot make your code a derivative of GPL code that must therefore also be released under the same license? If so, then under the terms of the GPL, must you include copyright notices and disclaimers?

GitHub’s assumption seems to be that using code suggested by Copilot is not a violation of copyleft licenses, because it is based on the training data en masse, not the work of any individual. However, that position causes its own problems. If GitHub is correct, Copilot becomes a means to sneak copyleft code into proprietary programs, making copyleft licenses ineffectual. This will result in challenges from institutions like the Linux Foundation or the Software Freedom Law Center, which might drag on for years, no doubt accompanied by conspiracy theorists reminding everybody that GitHub is owned by Microsoft. Whichever way you look at it, Copilot seems to be a recipe for chaos.

Hunting for a Solution

Julia Reda, a former German politician who advocates copyright reform and is currently a member of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, has blogged in detail about these alternative viewpoints. Her position is not at all what many free software supporters would like to see. Rather, she warns that applying copyright to Copilot’s position would be impractical and self-defeating.

To start with, Reda maintains that copyright infringement does not apply to small snippets of code. Rather, she maintains that copyright violation only applies when the “excerpt used is in turn original and unique enough to reach the threshold of originality.” Otherwise, accusations of copyright violations would be made constantly over trivial or unavoidable borrowings. Most borrowing through Copilot, she maintains, is likely to be too limited to reach this threshold, any more than short quotations in the media are copyright violations of novels.

Reda goes on to argue that while considering Copilot’s suggestions as derivative works would place them under the original copyleft licenses might be satisfying to free software advocates, this position would create its own problems. In particular, it would mean that all AI-generated material would also be subject to copyright. Although her suggestion that a music label might train “an AI with its music catalogue to automatically generate every tune imaginable” seems far-fetched, it would amount to an extension of copyright -- the exact opposite of what most copyleft advocates would desire. As she points out, companies at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) are already lobbying to apply copyright to AI-generated works, a change that would most benefit major corporations like Microsoft. In other words, in winning the Copilot battle, free software could lose the war.

However, Reda also rejects GitHub’s position. Code, she points out, is not the anonymous work of machines, but of individual coders. According to her, “Copyright law has only ever applied to intellectual creations -- where there is no creator, there is no work. This means that machine-generated code like that of GitHub Copilot is not a work under copyright law at all, so it is not a derivative work either. The output of a machine simply does not qualify for copyright protection -- it is in the public domain. That is good news for the open movement and not something that needs fixing.”

The trouble with this position is that Copilot would remain a means for bypassing the provisions of the GPL. In addition many free software supporters would not find Reda’s solution -- to leave things as they are -- acceptable, especially those who fear the hand of Microsoft behind Copilot. For this reason, the issues raised are unlikely to have a quick solution, particularly at a time when the Free Software Foundation is divided and attempting to reorganize. Will the corporations of the Linux Foundation move to protect their investment in free software instead? So far, the only thing that is clear is that the problem will not disappear easily or quickly.

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Nitrux 6.0 Now Ready to Rock Your World

The latest iteration of the Debian-based distribution includes all kinds of newness.

-

Linux Foundation Reports that Open Source Delivers Better ROI

In a report that may surprise no one in the Linux community, the Linux Foundation found that businesses are finding a 5X return on investment with open source software.

-

Keep Android Open

Google has announced that, soon, anyone looking to develop Android apps will have to first register centrally with Google.

-

Kernel 7.0 Now in Testing

Linus Torvalds has announced the first Release Candidate (RC) for the 7.x kernel is available for those who want to test it.

-

Introducing matrixOS, an Immutable Gentoo-Based Linux Distro

It was only a matter of time before a developer decided one of the most challenging Linux distributions needed to be immutable.

-

Chaos Comes to KDE in KaOS

KaOS devs are making a major change to the distribution, and it all comes down to one system.

-

New Linux Botnet Discovered

The SSHStalker botnet uses IRC C2 to control systems via legacy Linux kernel exploits.

-

The Next Linux Kernel Turns 7.0

Linus Torvalds has announced that after Linux kernel 6.19, we'll finally reach the 7.0 iteration stage.

-

Linux From Scratch Drops SysVinit Support

LFS will no longer support SysVinit.

-

LibreOffice 26.2 Now Available

With new features, improvements, and bug fixes, LibreOffice 26.2 delivers a modern, polished office suite without compromise.